TAKE TEN: Adriaan Esterhuizen

South African creative, Adriaan Esterhuizen, travelled to China to learn more about tea. The tea, it seemed, was so good that he decided to stay. We tracked him down to talk about street photography in China, the role of videography in his work and the benefits of taking a small little breather.

Hi Adriaan! Tell us about your work and why you are currently in China?

My work spans from photography to directing and editing video projects – from commercials and corporate shoots to branded content – though I’ve always been more drawn to documentary-style narrative projects.

In 2019, I travelled to China to learn about tea at its source. What started as a short documentary idea soon turned into something much bigger. I ended up in Guizhou, home to some of the world’s oldest tea tree species. That’s also where I met Rui, my partner, who was running a tea company called Grass People Tree. We’ve been working together ever since.

Together, we document and share stories about tea and the culture that surrounds it – a tradition that stretches back over 2000 years. We do this across various formats, including newsletters, social media content, and most recently, a biannual print journal.

While I’m based in China for most of the year, I continue to work remotely for clients and return to South Africa regularly for local projects.

In terms of doing street photography in China, are there specific rules you follow? Do you find people are accepting of foreigners photographing them?

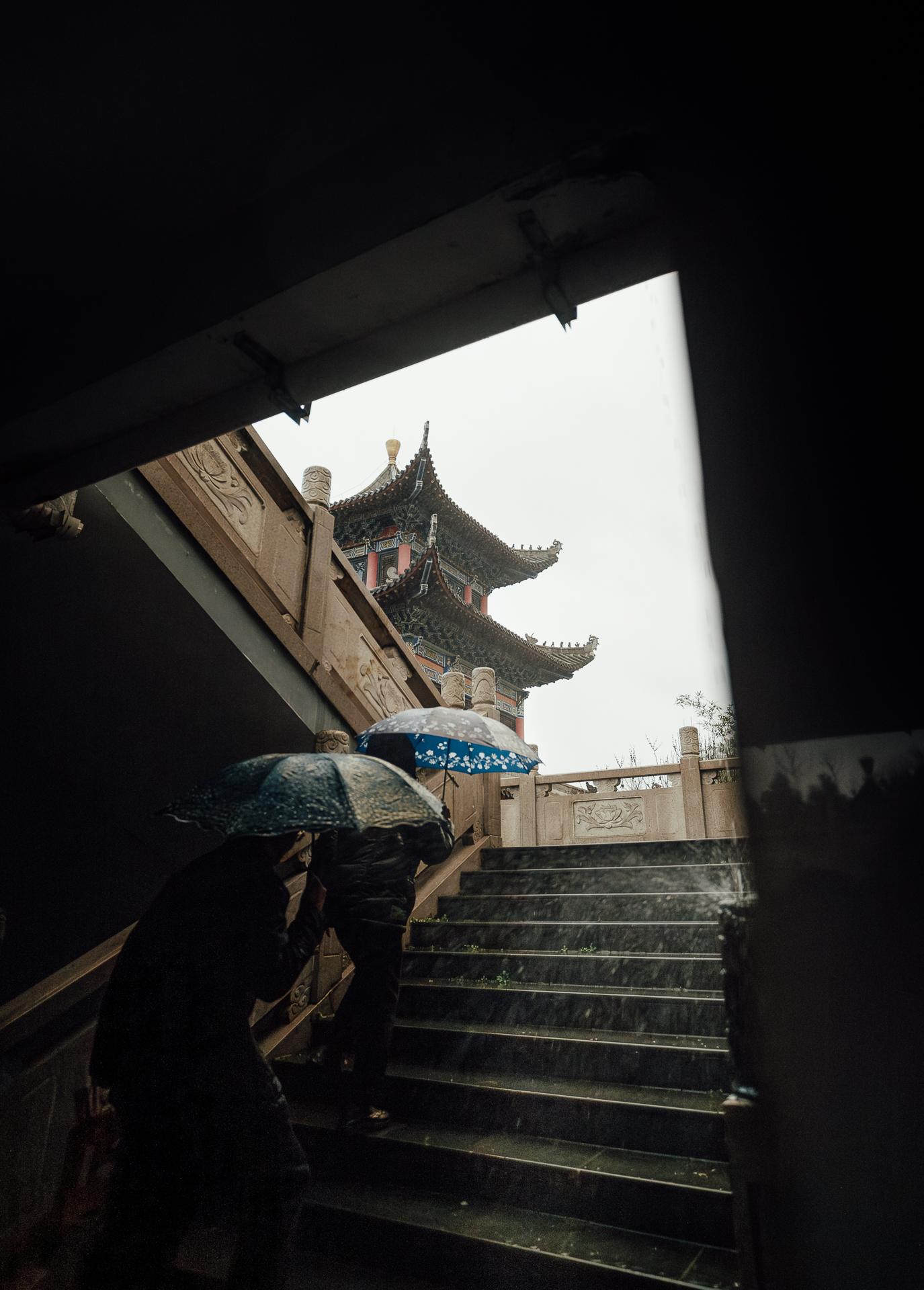

When it comes to street photography, I usually stick to one lens for a walk, keeping the gear and settings simple, it helps me stay present with what’s unfolding. I don’t really follow any rules, but I try to stay sensitive and respectful. A bit of eye contact, a smile, a nod – small gestures of connection make all the difference.

Here in Guizhou, people are incredibly welcoming. I’ve never been rejected or turned away, though I do get my share of stares, as I often find myself in places where few have encountered foreigners.

Guizhou has endured a long history of hardship, and while things are changing, there’s still a sensitivity to how the region and its people are represented. I try to remain mindful of that, so some of my favorite photographs will likely never be shared online. Some moments are better held quietly – not everything needs to be published to be respected.

Please tell us more about the gorgeous biannual journal you are involved with?

The journal is a project that my partner, Rui, and I created together, and it is very dear to us. It’s a biannual magazine that shares stories and insights about China rarely seen online. Named Grass People Tree (the same as Rui’s tea company), it goes beyond tea to explore life in China through language, photos, reflections, and stories about culture and traditions. Essentially, we want to hold a space where the beauty of everyday moments can be appreciated, but most importantly, to help bridge the perception divide between East and West.

I handle the visual side of the project while Rui writes, and together we carefully select stories that feel meaningful to us, reflecting both ancient wisdom and contemporary life. We’re now deep in the making of our second edition. The first was stocked in tea houses across the U.S. and U.K., and we can’t wait to show you what’s on the horizon.

What Fujifilm camera are you shooting with and which is your favourite lens?

I shoot with the Fujifilm X-H2S, and 90% of my work is done with the XF33mmF1.4, an incredibly underrated hybrid lens.

For the kind of fast, in-the-moment work I do in tea gardens or mountain villages, the 33mm is perfect: sharp, fast, with just the right amount of subject separation. It’s wide enough to frame a scene, but tight enough for portraits. It also has a surprisingly short minimum focus distance (around 30cm), which makes it ideal for close-ups, such as capturing the texture of tea leaves. It keeps my kit light and my pace fast – no constant gear-swapping.

Like many photographers, you are finding yourself also doing videography. From a shooting perspective, what were the biggest changes you had to make to accommodate the switch?

I actually have a background in multimedia and professionally started mainly with video, it was only a few years later that I got more serious about photography. I’m used to thinking in sequence, movement and sound, where you can gradually guide the viewer into a scene and build toward a feeling or story.

The biggest shift for me with stills was learning how to say something in a single frame, especially when it stands alone outside of a collection. Everything – emotion, meaning, and context – has to live inside one image. When you manage to capture that, it’s incredibly powerful.

What’s the one thing that most improved your photography and/or videography?

Learning to take a moment, especially in the middle of a busy shoot, can make all the difference. Whether in video or photography, that pause creates space to notice what wasn’t planned. Often, the most meaningful shots reveal themselves in those quiet, unhurried moments. Also, embracing shadows.

What are you trying to achieve with your photography and/or videography?

I don’t think there’s a single thing I’m trying to achieve. If anything, it’s about building bridges between subject and audience, between cultures and individuals. Cameras are such powerful tools for translating what words often can’t, especially across language barriers.

In this overwhelming, content-saturated world, I try to move slowly and deliberately; to document lives and experiences with sensitivity and depth. If my work sparks curiosity or shifts perspective, even slightly, that’s enough for me.

What’s the best thing about living in China?

Tea and China’s diversity. From indigenous cultures and regional food traditions to ancient history and new technology, it constantly surprises me. I often forget how vast China really is and how much I’ve only just begun to explore. Even after a few years in one province, I still feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface.

For local photographers looking to come to China, where would be the best places to visit?

I fell in love with southwest China. While not every region is easily accessible, provinces such as Yunnan, Sichuan and Guizhou offer an incredible mix of landscapes, cuisine and cultural depth. Their capital cities are also good entry points for first-time visitors, and the high-speed rail system makes exploring the surrounding areas affordable and straightforward. China is safe, efficient and deeply rewarding to travel, especially if you have the right apps and a bit of patience. I believe everyone should experience it at least once.

Find more of Adriaan’s work here:

Instagram: @homeforawhile, @thehouseofgrain, @grasspeopletree